The Science of Herbs ~

Minor updates/additions made June 21, 2022

Anyone who claims that “there’s no scientific evidence to support herbal medicine” clearly hasn’t been paying attention. Scientists have conducted hundreds of thousands of scientific studies on medicinal botanicals, and this data complements our long tradition (several millennia) of using plants safely as medicine. But to the general public and budding herbalists, this research seems locked away in a world of science, out of reach to the everyday person. The truth is, anyone can access the majority of this research. Once you get over a bit of a learning curve, you’ll better develop your understanding of healing plants and boost your science savvy.

Most of the scientific research you hear about in mainstream media comes through a filter. Some outlets are impartial, others incredibly biased, with the goal of either boosting herbal product sales or convincing you that herbs offer no value. By assessing the studies for yourself, you can break free of biased hype and draw your own conclusions. You just need to know where to look and how to interpret the data. First, let’s look at the different types of studies that exist and which ones provide the most useful information.

Rigorous Research

Since the 17th century, the scientific method has served as the standard for medicine. In contrast to anecdotal or experience-based medicine, this evidence-based approach is founded on the results of scientific studies. There are many ways to conduct studies, but the gold standard is the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical (RDBPC) trial. We’ll get into more specifics, but in a nutshell, this type of trial tests two or more groups of people with and without the herb, removes most potential confounding variables (outside influences that can affect the out- come), and assesses if an herb can provide any benefit, and if so, how much. This can really shed light on which herbs show potential in treating/alleviating a given health concern, and it helps determine whether an herb really does (or does not) provide the benefit (or harm) in question.

Unfortunately, studies are myopic in nature. They look only at a specific dose of a specific extract in a specific disease measured by specific parameters, and participants are viewed as a broad group, rather than as individuals. As a result, studies rarely shed light into all the various benefits or disadvantages of a particular herb or which type of person or situation might do best with this particular medicine.

The art of herbal medicine helps match the right herbs with the individual, taking into consideration his or her whole health history, symptoms, energetics, and constitution—something science alone really can’t evaluate very well. So, while scientific studies aren’t the end-all-be-all for practicing herbal medicine, they do serve as a very useful tool for learning about and understanding herbs.

Understanding Different Types of Research

While the RDBPC study is the most reliable type of study, only a fraction of the research being conducted falls into this category because it’s time consuming and expensive. I rely on human and review studies first, and turn to animal and lab studies only when more rigorous studies aren’t available.

Human Studies

Often called in vivo or “in life” studies, these involve human participants and therefore provide the most useful, applicable information on herbs. But even these have various levels of evidence or quality, as explained below.

- Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trials (most rigorous): The RDBPC study aims to prove efficacy, cause, and effect. These studies take two or more groups of people—at the minimum, one group that receives herbs and one that receives a placebo. They may also include a third group that’s given no intervention (the term used to describe the preventative or therapeutic measure being tested; i.e., the herb), a group given standard care/pharmaceutical drugs, and/or those given the drug plus the herb.

Randomizing ensures the groups are similar in their composition for things like gender, race, age, health habits, level of disease, and biomarkers of disease. (If one group has, say, an average of 60 an- gina attacks per month and the other experiences just 10, you’re not really going to know if the herb made a difference.)

Double-blinding ensures that both the study subjects and the researchers/doctors don’t know who’s receiving the real treatment or the “fake” placebo treatment. That’s to avoid placebo effect, in which participants believe they feel better or that a “treatment” is working based on their own expectations. Even the way a practitioner interacts with the client can influence perceptions and have a dramatic effect on outcome.

Double-blinding makes certain that the herb is not acting as a placebo. These tests are even more accurate if they’re conducted on large groups with hundreds or thousands of people rather than a small pilot study of, say, 10 to 30 people.Of course, you also have to examine the study itself. Did the re- searchers use a good quality product? What was the dose, frequency, and duration? What markers were they testing? - Clinical Trials (less rigorous): These studies may be very small in size and/or not include a control group. While they’re interesting and useful, they’re not as scientifically valid or reliable as RDBPC studies. You also need to be wary of bias in any study, but particularly with these, because they’re more apt to be driven by a company selling the product.

- Epidemiological Studies: These “population” or “observational” studies are popular for nutrition and, occasionally , herbs. They look at population habits in a non-scientific setting and don’t actually prove a cause and effect but only a correlation. But they’re easier and less expensive to conduct and can tell us what to follow up on with controlled clinical trials. For example, a study might survey Japanese people to tally data on green tea consumption and cognitive decline, with results that suggest (but do not prove) that drinking two cups or more daily correlates with a 50 percent decrease in dementia symptoms.

Animal & Lab Studies

These studies are far cheaper to run than human studies, with more rapid results. But the quality of the data tends to be poor because animals and lab tests don’t necessarily correlate to human doses and the way we metabolize substances when we consume them. Taking two capsules of ashwagandha daily in a human body is much different than administering some of the herb in rat feed or exposing the herb to cancer in a petri dish.

- Animal Tests are often inhumane (for example, forcing rats to swim until they drown to assess adaptogenic activity), and researchers sometimes need to kill them in order to perform a necropsy (animal autopsy) at the conclusion of the study. Aside from compassion and ethical concerns, a major problem with animal studies is that they usually use much higher doses of herbs per kilo- gram of body weight than a human would typically consume. I generally ignore animal studies in favor of human studies, unless there really aren’t human studies available. Even still, always take the data of an animal study with a huge grain of salt.

- Lab Studies can be conducted in a test tube, petri dish, or with human or animal tissue models. They’re usually the least applicable to real life; however, they help drive future research and shed light on the mechanism(s) of an herb’s action. For example, scientists might run some lab studies on the cancer- killing abilities of popular anti- cancer herbs used by an indigenous population to determine the one or two that have the best outcomes, and then pursue these plants with more rigorous study designs. Or scientists may show that, at least in a test tube or model, an herb re- duces inflammation via a particular pathway or chemical compound.

Review studies

This kind of study assesses and consolidates the data from a variety of studies to help reach a general consensus. They often provide the most useful data—especially since studies often conflict—and are usually easier to read and understand. Review studies can compile any type of study. The best review clinical trials, particularly RDBPC, compare the statistics in a “meta-analysis,” and may even report on bias in the research. Other review studies may provide a general overview of all the research present, including lab, animal, and less rigorous human studies, as well as some historical and traditional data.

Reading Scientific Studies

Don’t take a media soundbite at face value; they often spin the data to sound better or worse (depending on whether the outlet is pro- or anti-herbs). For instance, that hot new “arthritis” herb might not have actually reduced pain and symptoms at all, but only reduced a blood biomarker of inflammation. Or the urgent warning that St. John’s wort can cause phototoxic sun rash fails to mention that this data is based on the skin reactions of albino cows, who consumed the herb while grazing in the sun all day. Learning how to track down studies and getting used to the lingo puts the power in your hands.

For those unfamiliar with scientific literature, it can sound like ancient Greek. Don’t panic. First, focus on human clinical trials and review studies, which will be easier to understand (and more applicable and valid) than animal and lab studies. Then, tease out the basics:

1. What herb(s) did they use, and in what form and dose? Did they include a placebo or control group or did they compare it to a drug? (I love drug-herb studies. They show better results more often than herb-placebo studies.)

2. How long was the study?

3. What parameters did they test (i.e., blood results, client re- ports, or questionnaire results)?

4. What were the results? How did the herb compare to placebo or control group, if available? How much of an improvement (if available) was there?

Sometimes you need to look at charts in the full text to get a better understand- ing of results. A “significant” result might mean a mere 15 percent decrease in depression symptoms or weight loss that amounts to only two pounds over six months. That might be scientifically significant, but it’s hardly impressive.

Sometimes you need to calculate the results yourself from the raw data to see how impressive it actually was. Many studies (especially the well-designed ones) have “significant” results that still aren’t very impressive. Check out this calculations spreadsheet I made to help students. (Click “File” and “Make a copy” so you can edit your own file, then fill in the numbers from your study to automatically calculate the precent change and compare one group to another.)

Google can serve as an ally if you’re not sure what a specific scientific term means. Also note that the oft-reported “P-Value” in scientific results summaries has more to do with how replicable those results are rather than how impressive they are.

Where to Find Scientific Studies & Scientific Data

Find the Actual Studies

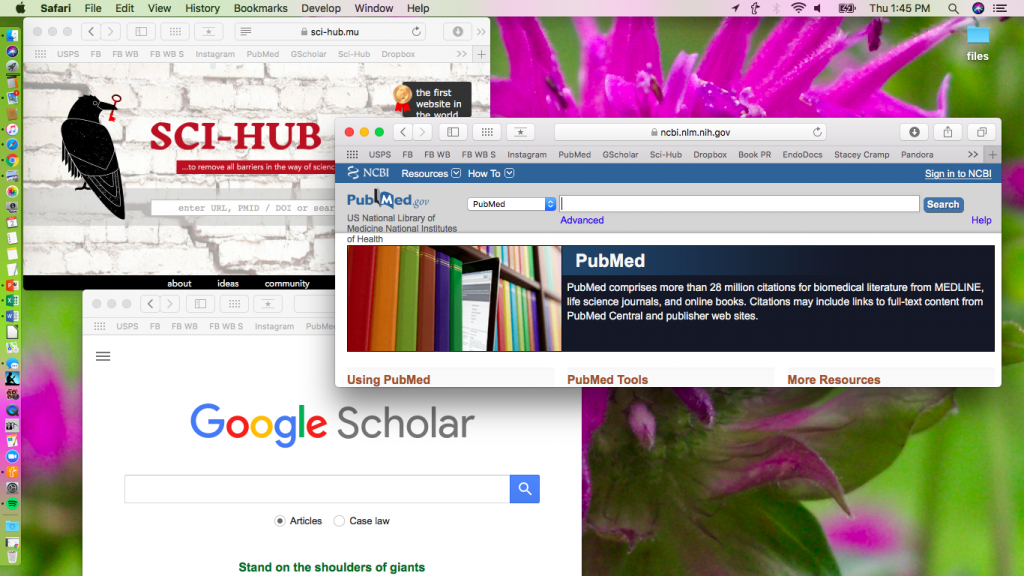

PubMed, maintained by the United States National Library of Medicine (NLM) at the National Institutes of Health, remains my favorite free, search- able database for scientific studies (mostly providing abstract summaries but occasionally offering links to free full-text versions). Play around with keywords, including common and Latin plant names and different words surrounding a health concern (e.g., “inflammation,” “pain,” “arthritis,” “osteoarthritis”). Once your search results come up, click “Clinical Trial,” “Review,” and/or “Human” to narrow it down and weed out less useful studies.

Google Scholar comes in handy when PubMed doesn’t get many hits. Plug in the exact study title to search for full studies, too (they appear in the right column with [PDF] – sometimes they open, other times they download to your computer when you click the link).

Sci-Hub grants access to full studies that you would otherwise need to pay for. This is moderately illegal. Because the companies that sell scientific studies and journals are constantly suing Sci-Hub, the exact website is always changing. Usually Wikipedia will show the most current access link. To use Sci-Hub, enter the DOI or PMID (which you can get on PubMed at the bottom of the abstract) into the search bar. Often, it will pull up the full-text study.

Other Options: Email the study author directly via contact info on the abstract or Research Gate to ask for a copy. Check with your alumnus organization to see if you have free access to journals through your college/university. Walk into a local medical library. Or pay for the full text via the journal site.

Read Study Reviews and Summaries

Other useful sites summarize evidence-based research (ideally with annotated study references so you can go back to the original studies if you so choose for more data). They’re usually easier to read than the actual studies and can help you find the right keywords. My favorites include:

- Memorial Sloan Kettering “Search About Herbs” has nice, detailed, even-keeled, and fully annotated summaries. Accept the disclaimer. Find your herb. Click the tabs (such as “clinical summary” under “for Healthcare Professionals” to open up the details on a particular plant profile.

- American Botanical Council/HerbalGram Some items require member access. HerbClips are ABC’s summaries of interesting herbal studies. HerbalGram articles are ABC-written articles and plant profiles. HerbMedPro is a database of studies – most require a membership but those by the Adopt-An-Herb program are free. The Botanical Adulterants Prevention Program keeps you up to date on herb adulteration issues. Their mailing list is great! Click on “register” on the top of the home page to sign up. Be aware that it’s more biased towards herbs due to how it’s funded, but they do a decent job remaining somewhat even-keeled.

- HealthNotes/Aisle7: Very herb-friendly, make sure to click the tabs to open up info. Be aware that it is more biased towards herbs due to how it’s funded.

- A.D.A.M. Nicely detailed though ultra conservative (sometimes overblown) on the cautions.

- I’m not a big fan of Medline/NCCIH – they interesting to look at but are incredibly biased against herbs and dietary supplements (even when the research is solid) and will over-blow unrealistic, barely substantiated cautions. WebMD is worse.

For more details on these sites and several other useful sources, see this section of my links page. You’ll also find additional evidence-based and scientific resources listed there.

Red Flags for Bias & Low Clinical Relevance

Sadly, most news media and many studies are biased or even fraudulent or at least misleading in their representations of study results. If you can, get ahold of the full text and also look at other studies on similar topics, when available. What matters most to us are those that are well designed nad show promising results with clinical relevance – a change that’s not just statistically significant but meaningful results for us as humans in the human body in normal human doses.

- Poor Study Design: Take these studies with a huge huge huge grain of salt: lab studies, animal studies, population/epidemiological studies, small human trials (like 6-12 people? really?), human trials that aren’t randomized or lack a control group (ideally they should be placebo-controlled, if possible).

- Wildly different results from different researchers, studies, or media outlets. Why? Is it the format, dose, duration, the populations and health concerns being studied? Or is it bias?

- Cherry-picked data. Both study researchers and reporters can pick the most dramatic results or studies to emphasize and ignore the rest. Looking at the study itself (versus a news report) and also looking at broader studies can help you guess when this is happening. Reporters love click bait. Researchers may have a pro- or anti-herb agenda.

- Wildly positive (or negative) results. If a study finds an herb had 80-100% improvements, that’s super cool… if it’s true. But look deeper because often these kinds of results are from baised or poorly designed studies.

- Study Results that are Not As Impressive As They’re Represented When You Really Look at Them. This can happen in abstracts and especially news reports. Often, the study is of low-quality design and clinical relevance – for example, a lab or animal study, population study, or small human study. But they might hide the type of study that it is and over-inflate results. Or perhaps the clinically relevant markers for change were not very impressive – for example, reduction of pain in people – but there was a slightly statically relevant change in lab markers like CRP. Saying ” inflammatory markers changed x%!” sounds a lot more impressive than “there was no difference in perceived pain in the intervention group versus the control group after four months.” Or that folks who dumped 1/3 of an ounce of very hot cayenne powder on breakfast (OMG, can you imagine?) lost 1-2 pounds after a few months of this. Or that folks who took green tea (in the form of a meal replacement shake) lost more pounds than those in the control group (who ate normal food however they wanted). Those are real studies I’ve seen. Or perhaps the two groups were wildly different at baseline, which reduces the validity of everything else.

- Conducted with a Brand Name Product. These studies are often funded or otherwise supported by the product company.

- Researchers on the Dole. It takes some digging – they’re supposed to disclose it but they don’t always or will make it less obvious (such as naming the parent company versus the product brand name), but if some of the researchers actually work for the company making the product or are otherwise invested in that product/company – this goes for big pharma as well as supplement companies – know that the study is going to be extremely biased. Often when you see the same researchers coming up multiple times studying that same product, there’s a good chance that they’re somehow affiliated with the company making the product.

- Look at Systematic and Meta-Analysis Reviews for summaries on (usually) the best quality designed studies to compare results. They may also provide useful charts and assessment on the studies and how biased or well designed they are.

- Consider Agenda. This is especially true for news outlets and reporters but can also be true for the studies and journals themselves. Who’s behind it? Do they have an agenda to push? Are there political motivations? It’s very common for extremist political news outlets (on both sides) to provide cherry-picked, poor quality, and/or over-inflated reports on a study. Even some medical journals are driven by political or product motivations.

A Word on Anecdotal or “Experience-Based” Information

People have been using herbal medicine quite successfully in a wide range of health conditions for millennia. This knowledge is based on direct observation of how plants affect people and disease, as well as the wisdom passed down from mentor to student and writer to reader. Scientists call this type of information “anecdotal” because it usually hasn’t been subjected to rigorous scientific testing methods. With so many variables, only a handful of cases, and issues surrounding placebo effect, it’s difficult to be 100-percent sure the herb will reliably do what you think it does for most people. That said, experience-based information tends to be more detailed, nuanced, and useful in our day-to-day life, forming a fuller picture of a plant and how it’s best used. Many things simply haven’t been studied. You’ll get this from classes, herb books and articles written by actual herbalists who use the plants for themselves and in their practices. In truth, I find this tends to be useful for everyday people and the budding herbalist, but I like to pair it with scientific evidence.

Maria Noël Groves, RH (AHG), is a registered clinical herbalist nestled in the pine forests of New Hampshire. She is the best-selling author of Body into Balance: An Herbal Guide to Holistic Self Care, and her second book on medicinal herb gardening, Grow Your Own Herbal Remedies, released in 2019.

This article was originally published in Herb Quarterly magazine.

Another version was published in Remedies magazine.