Potent Alcohol-Based Extracts ~

This blog contains all the basics for how to make tinctures with fresh or dry plants plus all sorts of helpful bonus calculations worksheets, a short fresh plant tincture video demonstration, and links to learn how to make less typical tincture styles (like percolation and double-extraction decoction tinctures).

Advantages of Tinctures

- Superior Extract: Alcohol is one of our best solvents available in the home kitchen that will extract most constituents from plants really well. Most tinctures are actually extracted in a combination of water and alcohol, but the water portion is not always obvious since it’s usually already present in spirits used (brandy and vodka are 40-50% alcohol and 50-60% water) or in the fresh plant material. Exceptions: Resins do best at high alcohol percent (70-95% alcohol), mucilage and polysaccharides extract best in water and can be destroyed or repelled by alcohol (tinctures are rarely used, but if you really want to make them, use 25-35% alcohol max). Alcohol does NOT extract an appreciable amount of minerals or fiber.

- Capture Fresh Plant Constituents: If you tincture a plant when it’s still fresh, you’ll extract and retain properties that might be lost or changed when drying. Using fresh plants is great for most plants but is particularly important for plants that dramatically lose potency once dried, such as lemon balm, skullcap, St. John’s wort, chickweed, and milky oat seed.

- Great Shelf Life: Unlike almost any other remedy, tinctures made with 50% or higher alcohol don’t really go bad (grow pathogens), and they usually retain potency for six to 10 years at least. Tinctures can lose potency over time and/or constituents may bind and precipitate out into glops or chunks (pigments and tannins especially… adding 10% glycerine to high-tannins plants like barks, cinnamon, and bacopa can help stall this). A few tinctures lose potency more quickly: Lemon balm and St. John’s wort are best within 3 years, while they retain their lemony flavor and red color, respectively.

- Fast and Superior Absorption: Alcohol enters the bloodstream quickly and basically bypasses digestion, making tinctures often more effective for delivering plant medicine more quickly and potently than, say, capsules, which rely upon digestion and liver metabolism for breakdown.

- Convenience: A dose of tincture can range from a few drops to 1 teaspoon, diluted in water (so the alcohol doesn’t burn your mouth). You can add it to something more flavorful if you prefer. Compared to tea, this means you get your dose over with quickly. So even if it doesn’t taste good, it’s done in seconds, and you can chase it with something to get rid of the flavor. It’s also only a small bottle to carry around.

- Easy Formulation: For the most part, you can easily combine any herbs (which have been tinctured separately, usually) together in a tincture blend without having to worry about flavor profiles, infusing versus decocting, etc. That said, resins will precipitate out into a sticky glop at the bottom of your bottle if you combine them with higher-water tinctures. And tannins love to bind to other constituents (alkaloids and other compounds), precipitating out in clumps over time – adding 10% glycerine to the blend can help slow tannins down. Most people tincture herbs separately so they can cater the extract specifically to that plant’s needs and then have total freedom in how to use or blend it. But, it is possible to tincture more than one plant together if you know they blend well and that you’ll want to use them in that format.

With so many pros, you can see why I’m such a fan of tinctures! That said nothing in life is perfect, and everything has pros and cons (this is the Capricorn/researcher/editor in me talking).

Disadvantages to Tinctures:

- It’s Alcohol: This is the main issue. Not everyone wants or tolerates alcohol. As long as you keep your dose under a teaspoon (and most people use just a few drops to 1 or 2 ml, which is less than half a teaspoon), you’re not likely to get buzzed from a tincture, and you can still use them with children safely. But if you have a past alcohol addiction, you may find tinctures trigger cravings – everyone is different, but why chance it if you don’t already know? (You can always use other remedy formats like tea, vinegar, powder, capsules, glycerine, oxymel, alcohol-free sugar syrup…) Some people avoid alcohol due to allergy, religious preference, personal preference, or other reasons as well. For a chart on how the alcohol in a tincture compares to booze, see the chart in the appendix of my book Grow Your Own Herbal Remedies or this Mother Earth Living article excerpt.

- It Doesn’t Extract EVERYTHING: While most constituents extract phenomenally well in alcohol, a few don’t. If you’re going for minerals (nutrition), mucilage (such as gut healing with marshmallow), polysaccharides (think: medicinal mushrooms), then tincture is not your best option.

- Some Conditions Are Better Met Via Different Formats: Tea is an obvious contrast. If you’re dealing with a urinary tract infection, you certainly can take herbs in tincture format, but using a more hydrating, flushing, soothing base (like tea or juice) will be better than alcohol. For gut healing and soothing, sipping a tea or broth or eating gruel will do a much nicer job delivering the medicine and coating the GI tract lining.

- Lacks Ritual: There’s something special about making, brewing, and sipping a cup of tea beyond just the herbs you put in it that doesn’t translate as well to “get it over quickly” remedies like tinctures and pills. While you will get some flavor and aroma from a tincture, sipping tea delivers those additional healing properties more effectively.

Tincture or Liquid Extract?

Also, let me explain a little herb lingo here. In stores, you typically see tinctures sold as “liquid extracts.” That’s because local pharmacy laws may prohibit herbalists from calling their remedies “tinctures.” But the term “liquid extract” is technically a vague term since any extract that’s in liquid form (vinegar, glycerine, water/tea…) could be called this. Hydroethanolic extract means it was extracted in water and alcohol, which is more descriptive and accurate for what we’re calling a tincture here.

(The CBD/cannabis community has confused things even more by selling liquid extracts in other solvents like oil that aren’t tinctures at all and labeling them as tincture. That’s another story altogether. Cannabis lingo is all over the map and often inaccurate or confusing.)

“Alcohol-Free Tinctures” are not actually tinctures at all but usually glycerites (extracted in glycerine), sometimes acetums (extracted in vinegar), oxymels (extracted in vinegar and honey), or other non-alcohol liquid extract. These usually aren’t as potent nor do they have as good of a shelf life compared to alcohol extracts, but they are an option for those who want or need to avoid alcohol.

How Do You Make a Tincture?

It’s ridiculously easy! Cover plants in alcohol so they’re completely submerged. Shake (macerate) regularly. Strain after one month, squeezing as much extract from the plant material as possible. You could strain it off earlier if you’re in a rush, and if you don’t strain it out for months, that’s fine, too. Alcohol is very forgiving. (Other solvents, not so much.)

Herbalists debate the best percent alcohol, ratio of herb to alcohol, and whether herbs should be fresh or dry. Sometimes it really does depend on the herb, but most of the time it’s personal preference. I personally find the methods I learned from Michael Moore most potent and effective, but play around and see what you like best.

Fresh Herb Tincture 1:2 in 95% alcohol

Chop up fresh herbs or roots, and stuff (really shove!) them in a mason jar until you can’t fit any more. Fill the jar to the tippy top with whole grain alcohol or high proof vodka or brandy. I prefer the highest proof I can get: 190 proof or 95% alcohol for fresh plants, but you can use the highest you can get (151-proof is next in. line, then 100-proof vodka, then your usual vodka or brandy, which is 80-proof). A day later, top the jar off again. Leave the jar in a dark place for at least one month (or as long as you like). Strain it out with a fine mesh strainer and muslin or cheesecloth to squeeze out the last bit. This method will give you approximately a 1:2 fresh herb extraction, meaning that for each ounce (weight, as shown on a kitchen scale) of herb, you add 2 ounces (volume, as shown on a glass measuring cup). Most herbs do well with a fresh tincture: lemon balm, echinacea, valerian… Most tinctures are shelf stable for up to 10 years, then lose potency. Also, don’t be alarmed if when you press out your herbs, you see little “black dots” all over your plant material. This is actually dark green plant pigments which has precipitated out and is not a problem nor any sign of your tincture going bad. I get this frequently with mint family plants like motherwort and lemon balm as well as some other plants.

Make sure your herb is totally covered with alcohol! The best way to do this is to choose the jar that fits the herb material exactly so you can shove it in and then pin it down with a lid. The fabulous and fun herbalist jim mcondald has a nice video further demonstrating this concept here. Also see my “Pick to Your Jar” cheat sheet at the end of this blog post.

Watch a Short Video of Me Making a Fresh Plant Tincture Here

You will notice that a 1:2 extract means I’m using a LOT of plant material SHOVED into the jar. The above two photos (of horehound and goldenrod, respectively) also show how much herb material I’m actually going to shove into the adjacent jar

Dry Herb Tincture 1:5 in 40-60% alcohol

Powder your herb in a food processor if it isn’t already in powder form. Per 1 oz (weight on a kitchen scale) of herb, add 5 ounces of alcohol/water mix. (Do NOT use whole grain alcohol unless you dilute it with distilled water.) The ideal alcohol/water ratio will vary by herb, but 40-60% (80-120 proof vodka or brandy) works for most herbs. Add about 10% vegetable glycerin for high tannin herbs like cinnamon. Combine your ingredients in a mason jar and shake your mixture as often as possible, aiming for 2xs/day. After no less than one month (more is fine), strain the mixture through a coffee filter-lined strainer. This is a 1:5 dry tincture. It works well for some aromatic herbs such as lavender, but is most often used for herbs that are primarily available dry: cinnamon, chocolate, cardamom, astragalus…

Straining Your Tinctures

You can strain these out through clean, tightly woven muslin or nylon cloth, several layers of cheesecloth, or a jelly bag (something not too absorbent), squeezing with your hands as hard as you can to get all the goodness out. I personally use a hydraulic stainless steel press (cheaper juice presses are also available online) so I can get a few extra ounces from my marc (“marc” is herb lingo for “spent herb”). But it’s really not necessary for a small-scale home herbalist. If you notice a lot of sediment in your tincture and want to strain it out (it’s not harmful to leave it there), then run the tincture through a coffee filter or let it stand and then decant. (Technically the above photo is of me straining herbs from oil, but the process is the same.)

Proof and Percent Alcohol – Making Sense of It

If you cut the proof in half, that will tell you the percent alcohol by volume. Generally we prefer relatively pure forms of alcohol (such as grain alcohol, organic ethanol, vodka) – which will have the best solvency – versus other types of alcohol (like whisky, gin) that have already extracted properties from herbs or barrels or have had other ingredients added to them already. But a lot of people do like brandy because it still works well and tastes smoother. Check your label – some brandy has artificial ingredients, and you also want to avoid flavored vodka. That said, you certainly can make a tincture in flavored vodka, whisky, tequila, etc. – it just might not be quite as potent.

| Proof | Percent Alcohol | Percent Water | Examples | Best For |

| 190 | 95% | 5% (neglibible) | Everclear, Clear Spring, Grain Alcohol, Ethanol (grain, sugar cane, corn, grape-based) | Fresh Plant Tincture, Resins, can dilute with filtered water for lower alcohol percent tinctures |

| 151 | 75% | 25% | Certain types of Everclear, Clear Spring, Grain Alcohol, Devil’s Springs Vodka (usually in states that don’t allow 190-proof) | Fresh Plant Tincture, Resins |

| 100 | 50% | 50% | Vodka (harder to find than regular vodka) | Dry Plants, also acceptable for Fresh Plant |

| 80 | 40% | 60% | Regular vodka, most brandy, many other types of spirits | Topical Liniments, Dry Plants, also acceptable for Fresh Plant |

Trying to figure out how to combine spirits/alcohol + water to reach a certain final percent alcohol??

Ouch, that math can hurt the brain. ***Use this calculations sheet*** and it will do the math for you! 😉

Where to Buy Alcohol

- Most liquor stores sell 80-proof brandy or vodka, 100-proof brandy, and higher-proof grain alcohols such as Everclear or Crystal Springs (may range from 150 to 190 proof depending on the state). Vodka or ethanol/grain alcohol are usually preferred but many herbalists like the gentle flavor of brandy – just note that some brandy contains artificial colors and flavors.

- If you want to buy organic, high proof, and/or large quantities of alcohol (which aren’t available in all states/liquor stores) the price per liter may be less expensive from…

- Warner Graham in Cockeysville, Maryland is where I buy organic sugar cane ethanol. They also sell other types and sources of non-organic and organic alcohol. Expect to spend about $350-500 per 5 gallon drum once federal excise tax and shipping are added. You’ll need to set up an account in advance and may need to fill out an application form and have a business ID.

- Culinary Solvent by Northern Maine Distilling Co in Brewer, Maine is extremely popular amongst my Maine and northeast colleges. Their local alcohol is made with organic non-GMO corn, in large and small quantities, and you can save on shipping fees (which are often as/more expensive than the alcohol itself) by picking it up at the company.

- Organic Alcohol Company in Ashland, Oregon offers easy online ordering for small and large businesses with a wide variety of types of organic alcohol (grain, sugar, grape, etc.) in various sizes. While it’s easy to order small quantities, you may find it more economical to just go for the larger drums.

- Fireside Distillers in Eugene, Oregon sells organic 5x distilled ethanol from corn, wheat, or sugar cane

The Math Stuff (Conversions & More)

Approximately….

1 ml = ~30 drops = 1/5 tsp = 1 squirt

5 sprays = 1 ml

30 is the Magic Number

A one-ounce tincture bottle holds 30 ml

One squirt from the dropper is about 1 ml

So, the 1 oz bottle has about 30 one-squirt (1 ml) doses.

If you prefer to pour the tincture, 30 drops (1 ml or 1 squirt) is also about 1/4 teaspoon.

Quick Conversions

- 5 ml = 1 tsp

- 30 ml = 1 oz

- 28 g = 1 oz

- 3 tsp = 1 Tbsp

- 4 Tbsp = 1/4 cup

- 1 cup = 8 oz

- 128 oz = 1 gallon = 16 cups

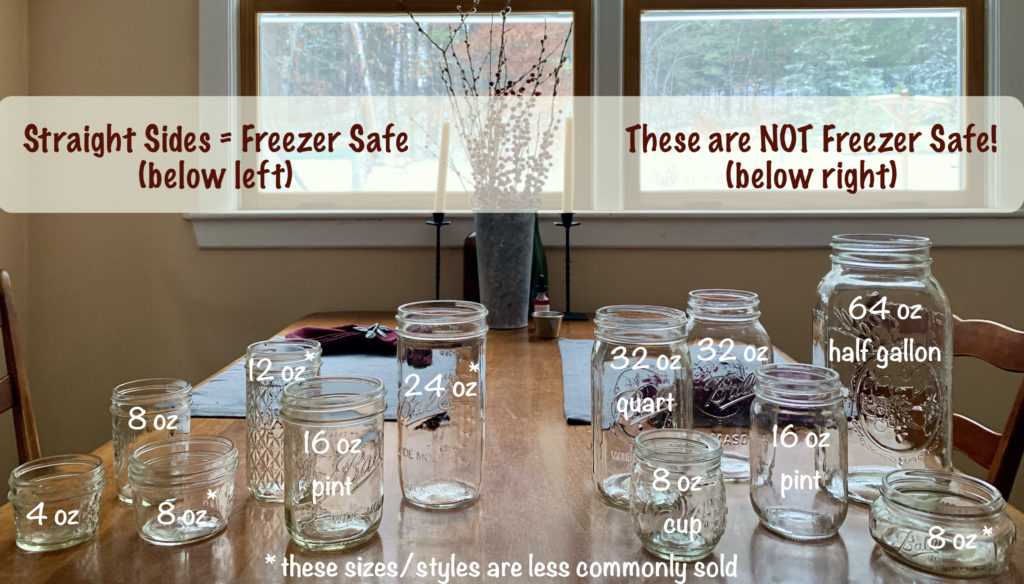

Pick to Your Jar & Needs

A quart of tincture lasts a LONG time.

Try to only make what you’ll use. Use this chart as a guide ~

| Jar Size | Weight of Herb (fresh or dry) |

End Result (varies widely) | |

| 4 oz (half cup) | 1 1/2 (1.5) oz fresh | 2/3 (.67) oz dry | 1-3 ounces |

| 8 oz (cup) | 2 2/3 (2.67) oz fresh | 1 1/3 (1.33) oz dry | 4-7 oz |

| 12 oz | 4 oz fresh | 2 oz dry | 6-11 oz |

| 16 oz (pint) | 5 1/2 (5.33) oz fresh | 2 2/3 (2.67) oz dry | 8-15 oz |

| 24 oz* | 8 oz fresh | 4 oz dry | 12-20 oz |

| 32 oz (quart) | 10 2/3 (10.67) oz fresh | 5 1/3 (5.33) oz dry | 20-28 oz |

| 64 oz (half gallon) | 21 1/3 (21.34) oz fresh | 10 2/3 (42.67) oz dry | 40-56 oz |

| 1 Gallon* (128 oz) | 42 2/3 (42.67) oz fresh | 21 1/3 (21.34) oz dry | 80-112 oz |

| divide jar oz size by 3 = each part (1 part for herb, 2 parts for solvent) | divide jar oz size by 6 = each part (1 part for herb, 5 parts for solvent) | ||

* Pasta sauce jars are often also 24 oz, and “gallon” jars often vary in exact quantity capacity. Measure by filling your jar with water, then pouring that water into a measuring cup to get the exact volume.

*

Tinctures Versus Pills?

It’s not an exact science, but…

1:2 = 1 gram herb to 2 ML of solvent

Each ml = 1/2 gram or 500 mg

1:5 = 1 gram herb in 5 ml solvent

Each ml = 1/5 g or 200 mg

See this Herbal Academy article for more on that.

Quick Formula for Figuring out Ratios

Read the following on a “wide angle” screen so it makes more sense (and just ignore me/don’t panic if this is all gibberish to you) ~

A C (B x C) ¸ A = D So… 1 oz 7 oz Recipe calls for grams.

— = — ——- = ——- You have 7 oz.

B D 28 g x So: (28 x 7) ¸ 1 = 196 g

My 5th grade math teacher would be so proud that I remember that lesson of hers…

Learn More

Percolation Tincture Method: This more complicated tincture method can only be done with dry herbs and you need a percolation cone, but it’s done within 24 hours (versus a month). Get the detailed notes (with full color photos) and the (long!) video here.

Decoction Tincture Method: For those mushrooms and minerals that don’t really extract well in alcohol, here’s a way to trick them into making a halfway decent shelf-stable alcohol extract by combining a hot water decoction (simmering) method with a tincture. Blog post here.

Simmered Still Glycerite Method: Want to make an alcohol-free glycerine extract? Check out this super cool method created by herbalist Steven Horne and demonstrated by Thomas Easley in this video. While you can use fresh plant material, it’s much less apt to spoil with dried material. Make sure to use distilled water and sterilized equipment to reduce the risk of spoilage as well.

Clinical herbalist Maria Noël Groves sees clients and teaches classes at Wintergreen Botanicals Herbal Clinic & Education Center in Allenstown, New Hampshire.

The statements made on this blog have not been evaluated by the FDA and are not intended to diagnose, prescribe, recommend, treat, cure, or offer medical advice. Please see your health care practitioner for help regarding choices and to avoid herb-drug interactions.

Minor updates made periodically to add extra charts, calculations, etc. Most recent update 2/2/23.

* this is an affiliate link – if you use the link, I will make a small commission at no extra cost to you